Stephen Macatonia directs Union Hand Roasted in London, one of the UK’s leading Direct Trade roasters. Last week he published this thoughtful piece in the Guardian — the latest contribution to the ongoing debate between advocates and practitioners of Fair Trade and Direct Trade over whose trade is fairest of them all.

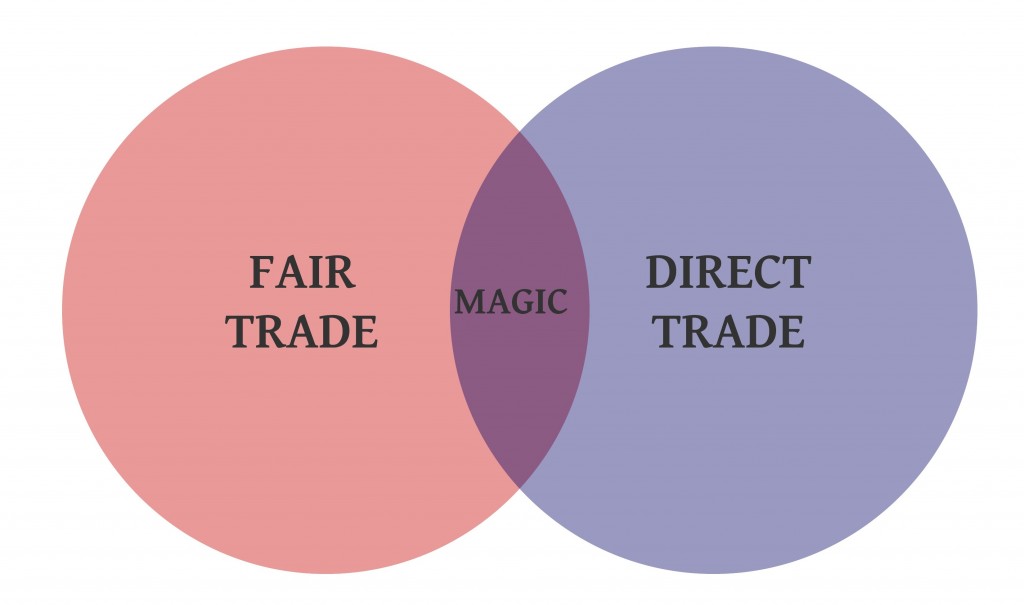

For our part, we like them both. And we like them best when they go together.

DIAGRAMS and FAMILY TREES.

I have written on the Fair Trade v Direct Trade debate here. And here. And here. And elsewhere. Probably more insightful than anything I have written are the contributions to those discussions by pioneers of both approaches to the coffee trade.

Peter Giuliano, who was involved in Fair Trade during the early days of certification in the U.S. market and knows a thing or two about Direct Trade as one of its intellectual authors, had this to say on the question of Fair v Direct:

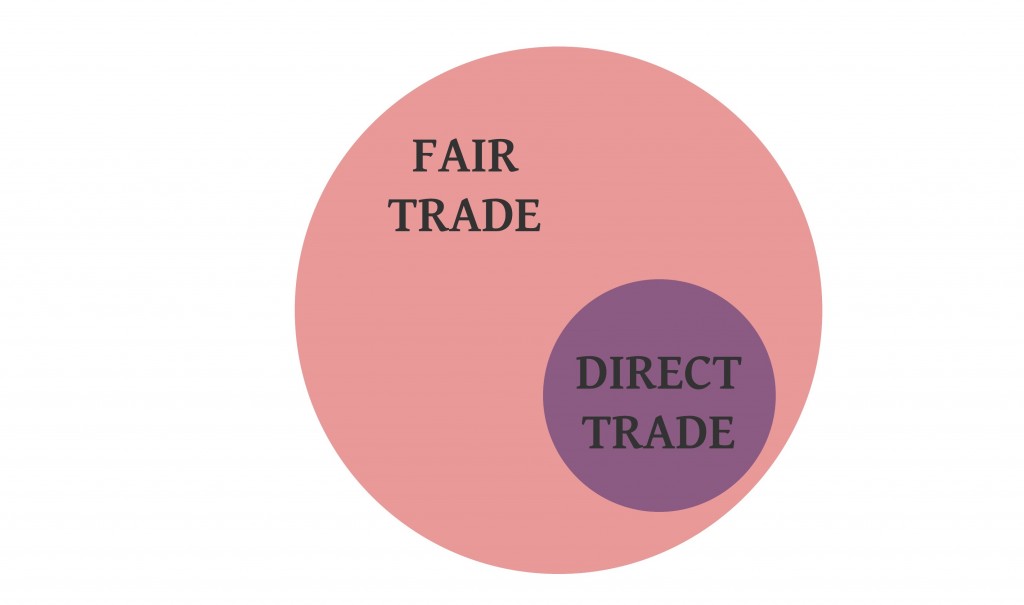

I believe that Direct Trade is a subset of Fair Trade, and therefore there is no Fair Trade vs. Direct Trade.

At first glance, that would seem to suggest that the appropriate graphic looks something more like this:

Except that Peter goes on to acknowledge that:

There are, however, Fair Trade Certified companies who don’t “do” the Direct Trade thing, and some companies use Direct Trade as a kind of substitute for Fair Trade in their language.

In other words, not all Fair Traders are Direct and not all Direct Traders are Fair. Meaning my diagram above may be a good way to think about how the two approaches relate to one another, after all.

I am sometimes tempted to think of the relationship between Fair Trade and Direct Trade genealogically — the family tree of sustainable coffee. Except it is not entirely clear which would lay rightful claim to its deep roots and which would be relegated to the branches, since the earliest Fair Traders were Direct and the earliest Direct Traders were Fair.

WHAT IS DIRECT TRADE, ANYWAY?

Stephen rightly acknowledges that Direct Trade is an ill-defined concept. He and the other roasters he mentions happen to be the kinds of Direct Trade roasters who spend an inordinate amount of time with smallholder farmers at source, sometimes investing in community development. But there are plenty of other self-proclaimed Direct Trade roasters who do not, and there is no Direct Trade certifier to police those roasters or verify their claims in the way that FLO and Fair Trade USA do for roasters who call themselves Fair Trade. This fact alone makes it hard to fairly evaluate Stephen’s contention that Direct Trade (whatever that means) is better for farmers than Fair Trade.

OFFER SHEETS v HANDSHAKES.

That is not to say that there isn’t a similar diversity of approaches to Fair Trade. There are Fair Trade roasters who have been trading with smallholder cooperatives for 15 years or more and have visited enough to be on a first name basis with more than a few of their members. And there are Fair Trade roasters who buy only Fair Trade Certified coffee off the offer sheets of their importers but have never been to a coffee-growing community. Their choice of Fair Trade Certified coffees represents a real commitment to fairness, but I often wonder whether a Direct Trade roaster who makes handshake commitments to farmers over kitchen tables in the coffeelands isn’t closer to the true spirit of Fair Trade, and doesn’t offer more value to farmers.

IS SMALL BEAUTIFUL?

If Direct Traders can agree on anything, I suspect it is the commitment to source only coffees of surpassing quality. That is good for the consumer, but may limit the social impact of Direct Trade on smallholder farmers: relatively few are able to consistently meet the exacting standards most Direct Trade roasters apply to their purchasing, and those who are usually sell only a small portion of their coffee into Direct Trade microlots.

COOPERATIVES.

Stephen points out that Fair Trade payments are made to cooperatives and not directly to farmers. This is true. But in most cases cooperatives offer their members commercial services like milling and exporting at more favorable rates than they would find at commercial mills. And cooperatives tend to offer a broader array of services than traders — beyond generating financial capital through the sale of coffee, coops invest in developing the human capital of their members and create social capital that members can draw on in times of need. It may be that the value of these services offsets any financial gains achieved through the kind of disintermediation favored by Direct Trade.

FALSE DICHOTOMIES.

Finally, Stephen contrasts “quality-centric” Direct Trade with Fair Trade, which he suggests does not create incentives for quality. I had hoped that when Roast Magazine awarded Microroaster of the Year honors to Fair Trade roasters two years running — Kickapoo Coffee in 2010 and Conscious Coffees in 2011 — it would have put that trope to rest for good.

These examples — and a growing number of others — suggest that roasters may choose to source Fair Trade coffee AND be obsessive about coffee quality.

Ideally, the terms Fair Trade and Direct Trade should help consumers in the marketplace make quick associations about the quality of the product they are purchasing and the impacts of their purchases on farmers. Which will be better in the cup? Which is fairer? Unfortunately, it may not be that simple. Consumers who associate Fair Trade with social justice and Direct Trade with cup quality may be slighting both — there are Direct Traders generating real social impact at source and Fair Traders delivering exceptional coffees in the marketplace.