There has been a lot of talk in recent months about coffee leaf rust in Central America, including plenty here on this blog. After months of talking with farmers, collecting data in the field, participating in international events, conferring with leaders in the coffee, government and research sectors, and investing private resources in a small-scale response in Guatemala, we are taking decisive steps toward responding to coffee rust region-wide.

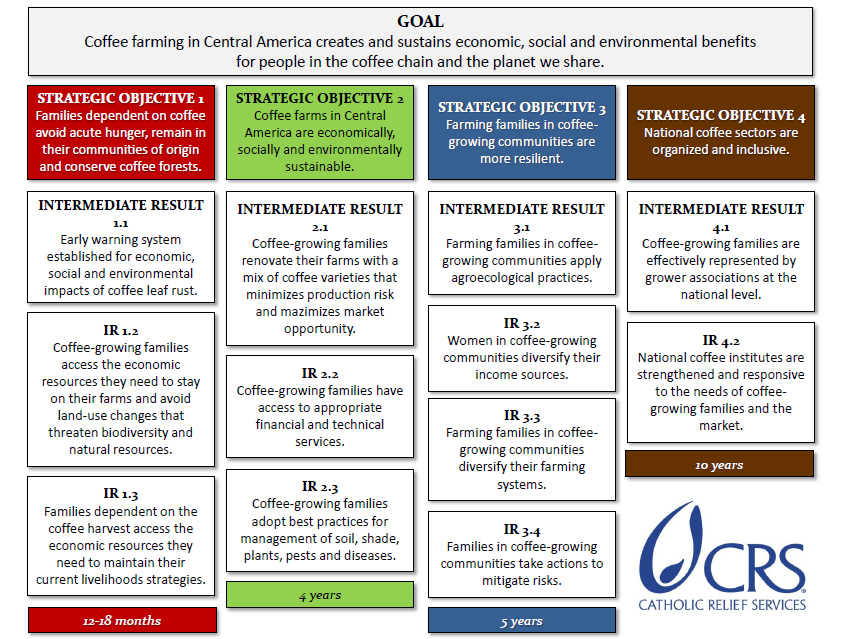

Last week I met with colleagues from across Central America to begin planning in earnest how CRS might be part of the collective response to rust. The key product of the workshop was this strategy map.

STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES.

- #1: Avoid hunger, migration, deforestation.

There are two key groups of people identified here–coffee farmers and their families on the one hand and coffee pickers and their families on the other–but the objectives we identify are the same for both: helping them avoid hunger, stay in their communities of origin and avoid livelihoods strategies that involve clear-cutting coffee forests. With coffee productivity and reduction in labor demand both set to double next year, we are deeply concerned about the first two; we have already seen evidence of the third this year in El Salvador. Short-term: 12-18 months.

- #2: Renovate massively and well.

The cost of renovation in Central America has been estimated at $800 million. Mobilizing funding on this scale is no small feat, but it is just the beginning. It must be delivered through financial products that are appropriate and affordable. Paired with qualified agricultural extension to ensure that farmers generate the returns they need on their investments in renovation. Tied to parallel efforts to expand the seed sectors throughout the region to meet the massive demand. And advanced in coordination with research and industry to ensure that growers are minimizing their production risks while preserving their market opportunities. Medium-term: 4 years.

- #3: Help coffee-growing communities become more resilient.

For this SO we were deliberate in the focus: not coffee-growing families but farming families in coffee-growing communities. We know that coffee growers have been dealt a bad hand with coffee rust, and that not all of them will double-down on coffee. Some will cut their losses and plant other crops. In some cases, this may be appropriate. Even if farmers do commit to reinvestment in coffee, they will be more resilient in the face of future shocks if they reduce their dependence on coffee for income. We are particularly excited about options for diversification that don’t require farmers to cut down forests that sequester carbon, conserve water resources and reduce the likelihood of natural disaster. Medium-term: 5 years.

- #4: Bridging farms and markets with inclusive research and extension.

There are critical gaps now in Central America’s coffee sectors, both in the organizational structures that link farmers to government agencies and coffee institutes, and in the capacity of those agencies and institutes to meet the needs of coffee growers. Investment in improving the governance of national coffee sectors and expanding the scope and quality of services delivered by national coffee institutes hold promise to generate returns all along the chain. A record of past failures does not seem like an compelling argument against trying to get it right this time around. Long-term: 10 years.

The coffee leaf rust crisis demands more than any of our companies, governments or organizations can give individually. Collaboration is essential–beginning with the planning process. Our consultations in recent months with farmers, researchers, roasters, coffee institutes, government ministries and nonprofits informed this draft strategy. But it is still a work in progress, and comments and critiques–particularly constructive ones–are always welcome.

– – – – –

ABOUT the RESULTS FRAMEWORK.

The results framework is a standard planning tool we use early in the project development process to map the upper-level outcomes project participants want to achieve.

The goal is generally ambitious–a long-term aspiration of significant scope to which a project might contribute but could never achieve on its own. The strategic objectives (SOs) are the highest-level outcomes a project can hold itself accountable for achieving and are significant in terms of scope and impact. And the intermediate results are really where the magic happens. These are the “behavior-change” objectives that collectively contribute–if a project is well-conceived–to the strategic objectives and drive toward a project’s goal. They are the result of lower-level goals around activities (what we will do) and outputs (what we will produce), but it is at the “IR” level that the human agency of participants kicks in and real change starts to happen.

This particular results framework is unconventional, as it is less a plan for implementation of a short-term project than a longer-range strategy map–the first draft of our thinking about what needs to happen in Central America over the next decade if the response to coffee rust is going to succeed not just in addressing this crisis, but in making farmers, communities and national coffee sectors more resilient in the face of future crises. We believe work needs to begin today on all four elements of the vision, but each will likely have a different duration. In the past I have suggested that the response to coffee rust is a relay race. Today I modify that analogy a bit–it may be a race in which all the runners leave the blocks at the same time, but run different distances.