Today I interview Adam McClellan, green coffee buyer for the iconic Portland-based roaster Stumptown, as we resume our series of conversations with specialty coffee tastemakers regarding their participation in our Colombian Varietal Cuppings.

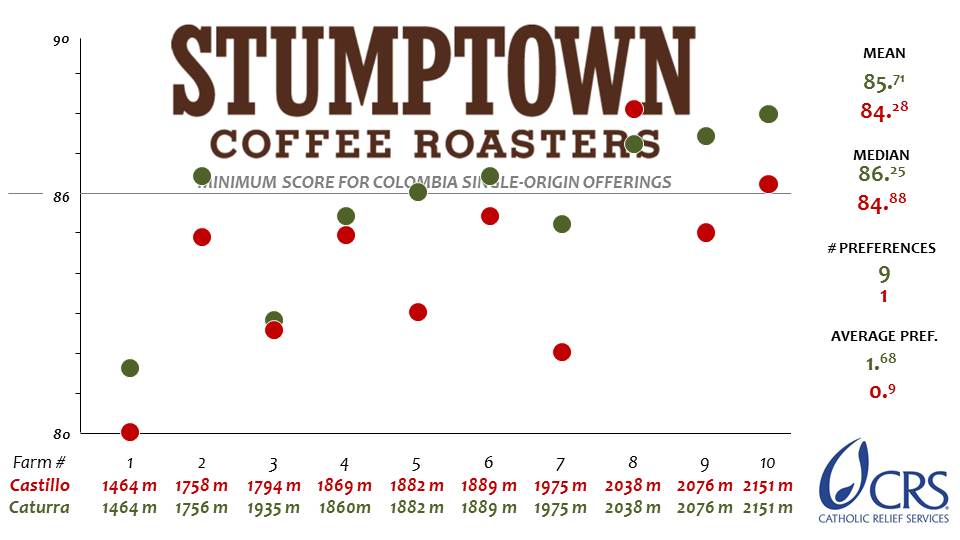

In September, together with Stumptown’s head roaster and quality control manager, Adam cupped sample pairs from 10 farms in Nariño participating in our Borderlands coffee project.

Going into the the head-to-head Castillo-v-Caturra cuppings, Adam and the Stumptown team preferred Caturra. Coming out of the experience, they still prefer Caturra. But the performance of the best Castillo samples raised an eyebrow or two in the Stumptown cupping lab.

Below, a summary of the Stumptown cupping results and a conversation with Adam about what those results mean to the company.

EXPECTATIONS…

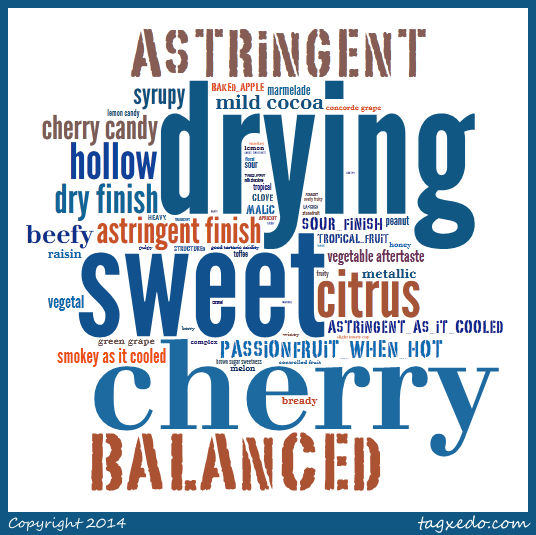

Before Adam cupped these coffees with his colleagues in Portland, I asked him to describe the company’s perceptions of the two varieties. He described Stumptown’s perception of Castillo this way: “when hot, this variety can present sweet, juicy characteristics, citric acidity, cherry fruit flavor notes with chocolate and caramel, but as it cools, tends to show more of its true character as astringent, dry, vegetal, with muted acidity. Some woody notes can also be present, but predominantly astringency and decreasing sweetness reduce final cup scores.”

…MEET REALITY.

After he cupped the coffees, I asked whether his perceptions were changed at all by the experience, particularly the high scores given to some Castillos and the references in the flavor notes to the cup complexity of some of the Castillo samples. He replied, “Yes, definitely. The ways I described my perception of Castillo before the cupping was how I thought of all Castillos. Now I realize there isn’t a singular Castillo profile, particularly in regard to what happens to the acidity as it cools.”

“I found that Castillos–especially those at 1900 meters or higher, where growers are able to process well–are complex coffees with a blend of acidities, not just the intense citric acidity that I associate with Castillo. I found lots of citric acidity but also malic and tartaric acidities in the best Castillos. It has definitely opened my mind a bit,” Adam concludes.

CASTILLO AND THE ELUSIVE VOCABULARY OF TASTE.

But Adam still harbors some concern about Castillo. “I still think Castillo has an aftertaste I can’t quite pinpoint: vegetal, metallic, astringent, drying.”

He may not have felt confident in his sensory vocabulary on the day of our interview, but a look at the flavor notes from the cupping shows that he and his colleagues did consistently find these traits in the Castillo samples. Note the prominent reference in the histogram below of “astringent” and “drying,” and the specific if less pronounced references from left to right around the middle of the graphic to “dry finish,” astringent finish,” “sour finish,” “vegetable aftertaste,” “metallic,” and “astringent as it cooled.”

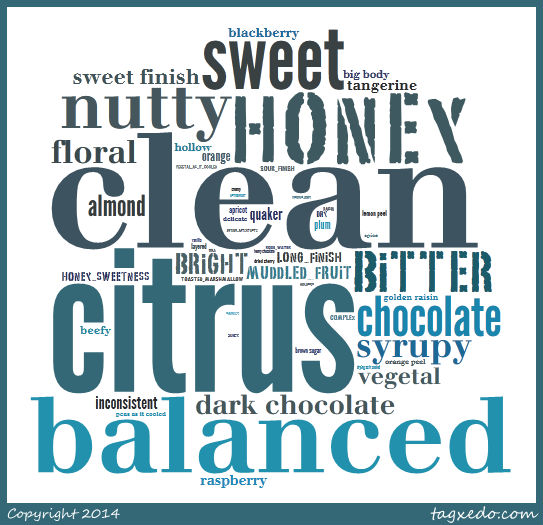

The histogram for Stumptown’s Caturra flavor notes, by comparison, shows comparatively fewer negative attributes and none related specifically to the coffee’s finish.

FROM PORTLAND TO CHICAGO

In addition to cupping these 10 sample pairs with his Stumptown colleagues in Portland, Adam cupped 21 sample pairs two times each with an illustrious panel of cuppers in Chicago as part of the Colombia Sensory Trial.

There, Adam again gave Caturra the edge in overall average score, but by a narrower margin (down from 1.4 points to 0.4 points). He preferred Caturra less frequently (down from 90 percent to 52 percent). When he did prefer Caturra, though, he preferred it by a bigger margin than the team in Portland (up from 1.7 points to 2.4 points).

SO, WHAT?

Overall, Adam doesn’t feel like the exercise will change his buying perspectives or Stumptown’s buying practices in any radical way.

“Our preference, as it pertains to cup quality and purchasing, was and will remain to look for coffee from Colombia with as low a percentage of Castillo as possible,” he said. “When establish quality parameters with growers and exporters, we look for areas and producers with potential to deliver single-variety lots of Caturra, Bourbon, and Typica, or blends with a higher percentage of these varieties. We feel this gives us a better success rate at approving samples, getting higher cup scores and returning price premiums to growers.”

A NEW VIEW OF CASTILLO?

He feels that the results of this exercise validate Stumptown’s position at the same time that they show Castillo capable of things the company didn’t think it was capable of. “I was happy to see a few Castillo samples de-bunk my previous belief that an 85 was the maximum score Castillo could achieve on its own, and score 86+,” Adam said. When I asked him why that result made him happy, he said this: “Because there is so much Castillo being planted that we will need to buy it whether we like it or not, and we are always looking for coffees scoring 86 points and up.”

Adam is quick to point out that 85 points is a “really good score for specialty coffee in general,” just not up to Stumptown’s standards for single-origin Colombian offerings–the kinds that earn growers premiums.

Stumptown believes growers in Colombia will continue to plant more Castillo. While Adam understands the reasons why, he also hopes that even as grower convert more of their farms to Castillo, they continue to reserve plots for the traditional varieties Stumptown seeks.

“I understand very, very clearly why a producer would want to plant Castillo, and I will always give it a fair shake on the cupping table. But I do belive having more than one variety is advantageous for growers selling to buyers who value cup quality,” he says. “Like many buyers out there, we are cupping all the coffees we buy and basing price premiums on scores. If traditional varieties are consistently delivering higher scores, growers who want to work with companies like ours would do well to continue planting them on at least a part of their farm.”

Adam fears that growers may be giving up too soon on Caturra and other varieties susceptible to coffee leaf rust. “Caturra can be very well managed,” he says. “I have seen a lot of farms in southern Colombia managing rust effectively. We pay our exporter to deliver customized agronomic assistance based on the results of soil analysis, and the results have been impressive. I don’t think Colombia needs to give up on Caturra, I think it needs to deliver the right kind of technical assistance to growers who want to continue to work with it.”

Besides the market rationale for growers to diversify the varietal mix on their farms, Adam believes there is a strong agronomic argument to be made for not giving farms over entirely to Castillo. “I am not an agronomist,” he says, “but I think the record is pretty clear: rarely in the history of agriculture has planting one variety of one species been healthy anywhere.”

.

This conversation with Adam McClellan of Stumptown Coffee is the third in a series of weekly interviews on the CRS Colombian Varietal Cuppings.

<< Last post: Intelligentsia

Next post: George Howell Coffee >>

– – – – –

The Colombia Sensory Trial and the CRS Colombian Varietal Cuppings are supported by a grant from the Howard G. Buffett Foundation.