At The SCAA Event last month, our CIAT friend and colleague Mark Lundy presented the results of costs-of-production research we did together on the basis of 2013 data from our Borderlands Coffee Project in Colombia. Today I explore with Mark what we learned from those data and what implications they may have for coffee buyers and policymakers.

The four top-level takeaways are these:

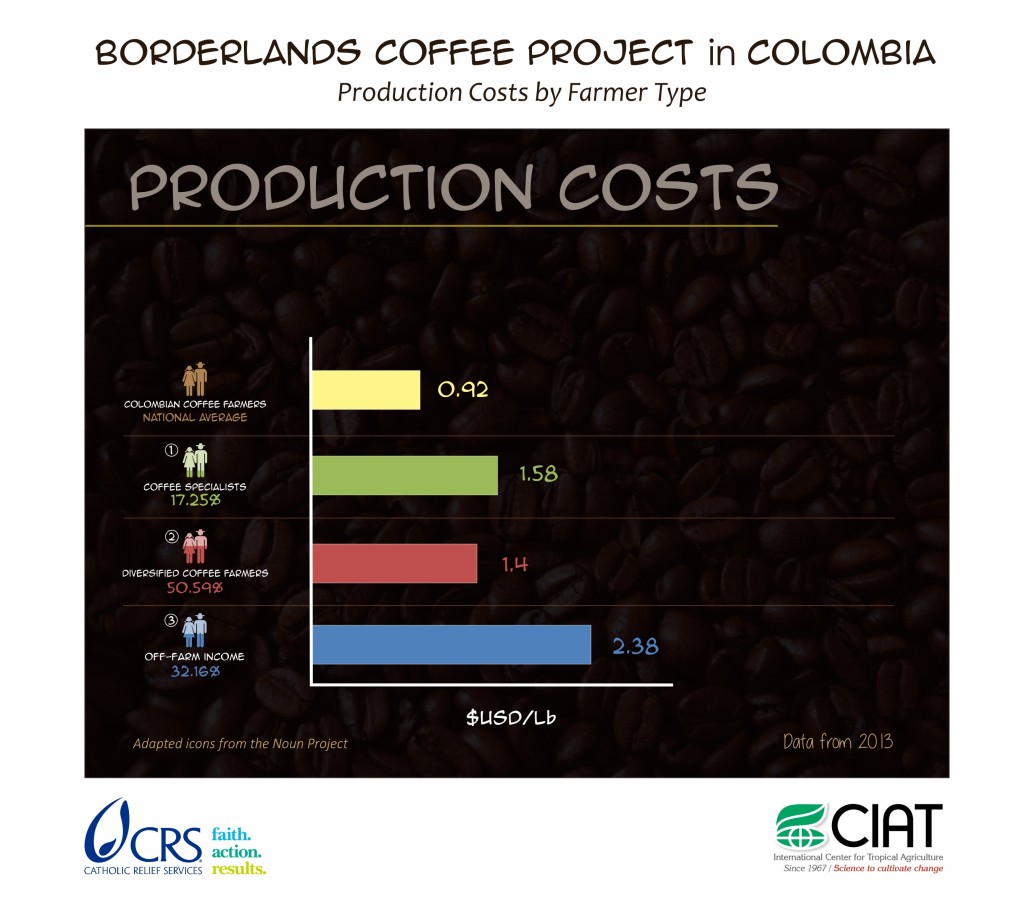

- Think costs of production, not cost of production. There are different kinds of farmers with different efficiencies and different costs of production. Relying on averages may be convenient, but Mark suggests it can also be “dangerous” since it obscures important differences between different types of farmers and may lead to inaccurate conclusions about farm-level profitability.

- Farmers seemed to turn a profit on their coffee only when they earned substantial price premiums for quality-based differentiation. This preliminary finding needs further validation, and is based on data for one year in one region with notably low yields and farm efficiencies. That said, it is a source of concern given that relatively few growers are able to access premiums of this nature.

- Coffee buyers interested in long-term relationships need to understand the costs of production for the specific growers in their supply chains. If these growers are going to bet their futures on coffee, buyers need to create the kinds of incentives growers need to be profitable and sustain that profitability over time.

- Policymakers should note that smallholder coffee farmers have narrow (and often negative) margins and channel resources to initiatives that will boost farm profitability—including improved extension to increase yields and farm efficiencies and expanded access to higher-value segments of the coffee market.

.

THE METHODOLOGY

The data for this research were collected from smallholder farmers in Nariño through three specific mechanisms of our Borderlands Coffee Project:

- Baseline data from this rigorous survey we conducted with CIAT in 2012

- Cuadernos de cuenta—field logs in which growers kept detailed records of every coffee-related expense and each sale of coffee

- Focus group discussions with project participants

Through the triangulation of data collected through these three channels, we were able to generate accurate estimates of production costs in Nariño. This approach is pretty standard. But there were two wrinkles in this case that may make the analysis even more valuable than traditional cost-of-production research.

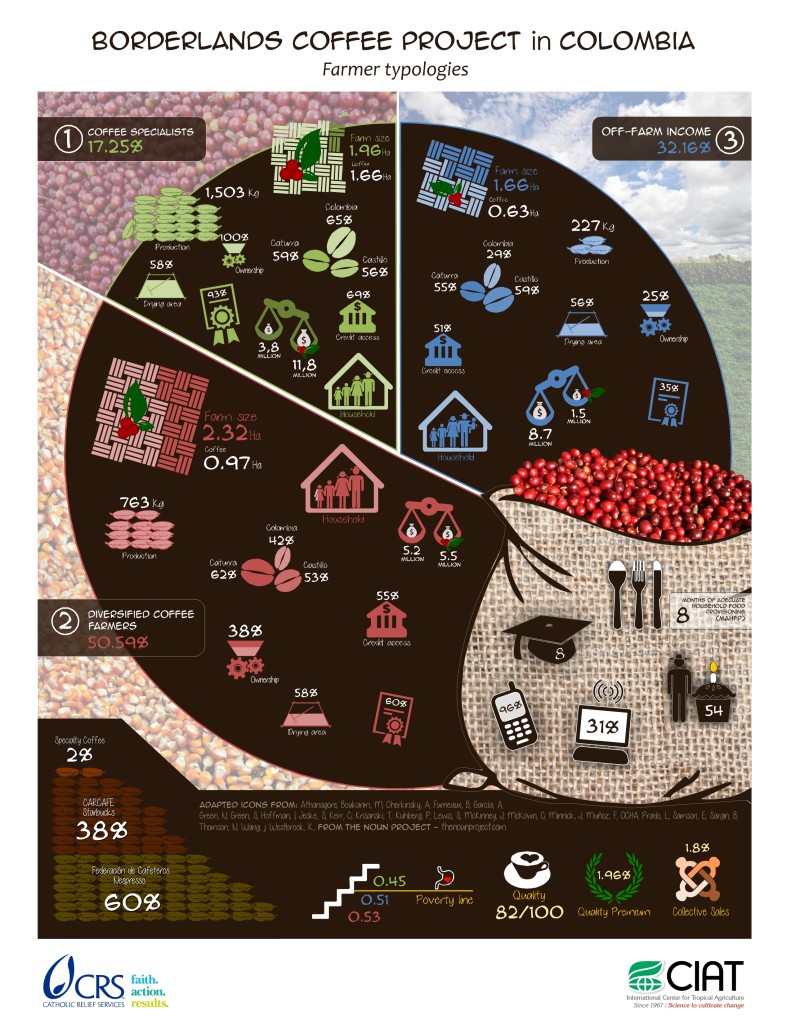

Farmer Typologies

The first wrinkle is this: we identified three farmer typologies through our baseline survey—specialized coffee growers, diversified farmers and farmers who earn the majority of their income off-farm, from salaries, remittances, piece-work or other activities.

.

.

Each one has different level of dependence on coffee for their income, a different cost of production and a different return on their investment in coffee. Specialized coffee farmers have the most area devoted to coffee, the highest production and rates of productivity, the highest incomes overall, the highest coffee incomes (both in absolute terms and as a percentage of total income) and are most likely to own processing equipment, hold a high-school diploma and have access to credit. They are least likely to be poor. This disaggregation added an important dimension to our analysis.

Farmgate Price Data

The second are the farmgate price data we collected from project participants after the 2013 harvest. “The interesting thing about this work was that we actually had sales price data, and not just for prevailing market prices in Nariño,” Mark says. “We also had info on other prices as well which is somewhat novel.” In other words, CIAT’s economists and researchers could match real production costs for specific farmers to real prices paid.

.

COSTS of PRODUCTION > COST of PRODUCTION

The most important finding of the research is that we should not be talking about cost of production but costs of production. Different kinds of coffee growers have different efficiencies and different costs of production and these differences get lost when data are aggregated.

.

.

Colombia’s Misión Cafetera included very detailed cost-of-production data from each of Colombia’s coffee-growing departments in its final report. They may be necessary but not sufficient, Mark says, for buyers to have an accurate picture of what is happening in their own supply chains: “These data are important, but because they are averages they tend to obscure differences in production costs across different types of farmers.”

.

COFFEE BUYERS: KNOW THE COSTS OF PRODUCTION IN YOUR SUPPLY CHAINS

For Mark, the implications of this research for industry are clear.

“Be clear about who is in your chain and what their real costs of production are, particularly if you are interested in being in business over the long term,” he says. “You need to understand the return on investment in coffee for farmers in your supply chain and whether or not they are able to make a living. People make a lot of noise about relevo generacional—the fact that many young people born into coffee are choosing not to stay in coffee but migrate to cities. All of this comes back to the fact that if people doesn’t have clear signals and incentives to stay in coffee, they won’t bet on coffee over the long term.”

.

THE IMPORTANCE (AND LIMITATIONS) OF PREMIUMS

The data show that for most of the coffee sold by project participants, production costs exceeded the prices they earned. The lone exception was the microlot segment.

.

.

“I would be careful not to overstate the case,” Mark says. “These are 2013 data, taken from one year in one small area of Colombia. The data from 2014 may tell us something different. But yes, these data do show that that harvest year, the only profitable segment of the market was the microlot segment.”

He hastened to add that “One-off price premiums don’t necessarily achieve the goal of profitability. These are agroforestry systems that are incredibly sticky. People can’t respond very quickly to market signals because it takes time to make changes and see results in that kind of production system.”

Add to that the fact that many growers fail to achieve microlot quality year-on-year, and it is no wonder the quality strategy isn’t for everyone. “The decision not to specialize in coffee can make sense under conditions of market, climatic and price uncertainty,” Mark says.

Coffee buyers who want growers in their supply chains to specialize in coffee need to create stronger incentives and sustain their commitment to those incentives over time, Mark says: “What is needed is incremental and sustained change backed by investment of time and money from the market.”

He cites the example of the ASPROTIMANA organization in neighboring Huila, which has had success selling into higher-value segments of the coffee market. Its members have achieved yields of over 20 bags per hectare while their neighbors are producing between 8-9 bags, similar to the yields we found through our baseline study in Nariño.

“It’s just one case,” Mark says. “But this is what I am talking about. If buyers who want access to consistent volumes of high-quality coffee can create the proper incentives, growers will respond.”

.

POLICYMAKERS: MIND THE MARGINS

So the implications for industry are clear: know the costs of production in your supply chain and understand what they imply for the profitability and sustainability of supply. When I asked Mark what he thought the implications were for public policy related to the coffee sector, which in Colombia is set by the Federación Nacional de Cafeteros, he said this:

“Our COP study, as well as the tables in the Mision Cafetera report on COP, should raise concerns in the public sector regarding the thin margins producers receive. Clearly the direct subsidy strategy employed in the past is not sustainable and the transition towards higher value markets remains slow and with clear limitations. For me the big question is how to retool the institutions of the coffee sector to gain in efficiencies and deliver on outcomes like increased productivity, better market linkages and incentives, and more effective extension strategies.

“At the end of the day Colombia needs to increase its productivity to lower costs and remain competitive even in lower quality, higher volume segments of the market. That is not just true in Colombia, but tends to be true for smallholder coffee farmers everywhere. What Colombia may have that other countries do not are clear opportunities to move some production into higher value segments based on quality, but the basis to make any of this really transformational is still improved yields.”