Over the past two days, I published this summary of a peer-reviewed study based on data from our Borderlands project in Colombia and this interview with the study’s lead author. Today, I extract its key insights on farm labor, which include a characterization of farmworkers in the coffeelands as poorer and less educated than certified coffee growers, with larger families and smaller farms set farther from the nearest cities.

.

ALLOCATION OF LABOR.

The research was designed to examine the impacts of coffee certification on household livelihoods strategies. Specially, it looked at how families allocate their own resources—principally their labor—across five different kinds of income-generating activities: (1.) coffee, (2.) farming activities other than coffee, (3.) self-employment outside of agriculture, (4.) agricultural wage labor, or farm work, and (5.) wage labor outside of agriculture. This post focuses on the factors that the study shows to drive families to allocate labor to the fourth category, farm work. It includes both positive (+) and negative (-) relationships and cites key passages of the study to support each finding.

.

KEY DRIVERS OF LABOR-ALLOCATION DECISION

Income (-)

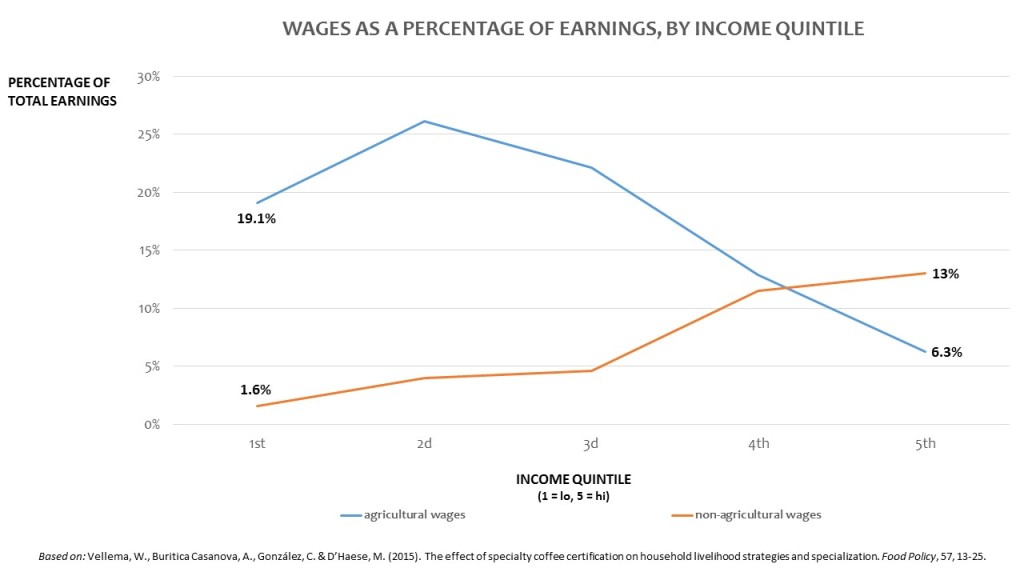

This graph shows clearly the negative relationship between income and reliance on farm work (and the positive relationship between income and reliance on wage labor in other, higher-paying sectors that likely have higher educational requirements). There is likely a self-perpetuating dynamic at play here: the poorest farmers depend most on low-paying farm work because they have low levels of education and few other opportunities; the poorest farmers have low levels of education and few other opportunities because they depend on low-paying farm work.

.

.

Education (-)

“Education reduced the likelihood of participation in agricultural wage labor.”

“The negative effect of education on agricultural wage labor is most likely due to the substitution of labor away from this activity” to other activities with higher returns.

Land holdings (-)

Farmers with more land earned less from farm work than farmers with less land. The authors argue that the negative relationship between land holdings and farm work are suggestive of “push diversification”—farmers seek opportunities for wage labor on other farms not because they want to, but because they need to; their farms aren’t large enough to provide a living. And this even though the returns to that allocation of labor are notoriously low. The authors write, “Households with land holdings too small to generate sufficient income have to work on other farms, even if obtained wages are low.”

Household size (+)

“Household size was positively related to engagement in…agricultural wage labor.”

This finding is perhaps intuitive, as smallholder farming families with little land of their own are less likely to provide full employment on their own farms to all family members if those families are large.

Distance from nearest city (+)

“Households living further away from cities are more likely to be involved in agriculture, both on- and off-farm.” In other words, the farthest-flung families are most likely to be farmers who also sell their labor on neighboring farms.

Coffee certification (-)

“Coffee producers with farm certification were…less likely to participate in agricultural wage labor.”

.

WHO ARE THE FARMWORKERS IN THE COFFEELANDS?

The study generates a characterization of farmworkers in the coffeelands that isn’t pretty: they are the people in the coffeelands who are poorest and least educated, with the biggest families and the smallest farms, living farthest off the beaten path.

It also suggests that farmworkers are not likely to be the same people as the specialized coffee farmers who participate in specialty coffee supply chains—a group of farmers who are more likely to be working on their own farms than the farms of other people.

Taken together, these insights suggest that the farmworkers on which specialty coffee depends are more vulnerable than smallholder farmers in specialty coffee supply chain. They also suggest that unless we have made a concerted effort to encounter coffee farmworkers in our trips to origin, we probably haven’t had much contact with them.