Brazil’s fight against modern slavery has been held up as an example by labor rights advocates from Free the Slaves to the U.S. Department of Labor to the UN’s International Labor Organization. Its effort has been ambitious (the goal is total eradication of modern slavery), courageous (websites have been hacked, activists threatened, inspectors killed), creative (prevention campaigns include radionovelas, comic strips, video games and educational materials for schools) and cross-sectoral (public, private, multilateral and non-profit sectors are all deeply engaged). Most importantly, it has been effective in generating actionable information, preventing new cases of slavery and rescuing workers who have been enslaved.

.

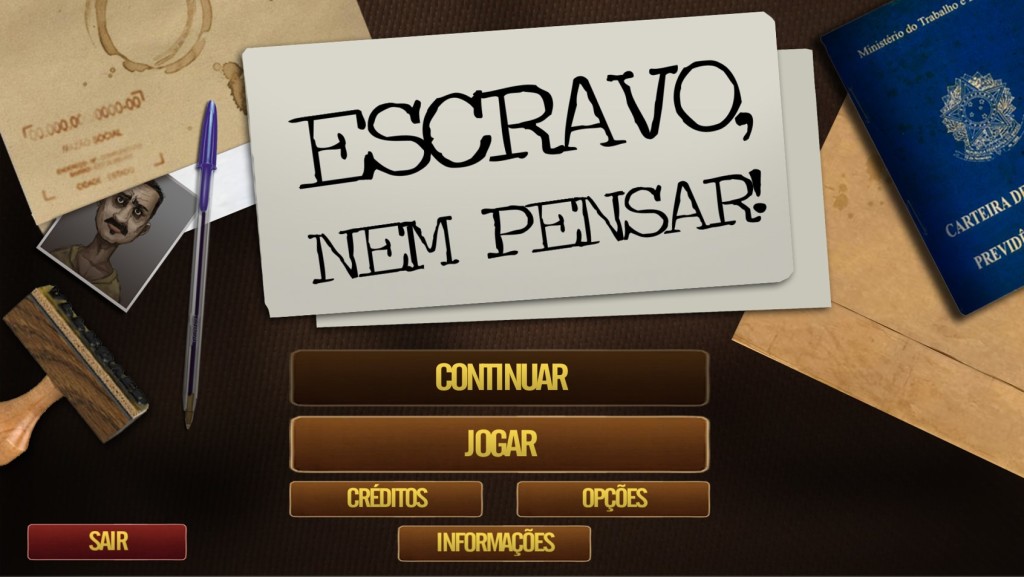

“Escravo, Nem Pensar!” is a creative campaign led by the non-profit Repórter Brasil that is designed to prevent modern slavery that has enlisted a broad range of communications tools to raise awareness, including this video game.

.

ORIGINS

The Pastoral Land Commission (CPT) of Brazil’s Catholic Church, behind the notable leadership of the Dominican friar Xavier Plassat, was instrumental in the government’s reluctant recognition of the existence of modern slavery in Brazil. The CPT was courageous in its front-line accompaniment of victims of abusive labor practices in the Amazon and relentless in issuing denunciations to the government and international forums beginning in the mid-1970s. In 1995, largely as a result of its advocacy, Brazil’s government acknowledged the country had a modern slavery problem.

That same year, Brazil launched a comprehensive effort to end modern slavery. Over the past 20 years, that effort has involved all three branches of Brazil’s government, leaders from the private sector and a mix of front-line work and creative campaigning by non-profit organizations. Key elements in that effort are profiled below.

.

MINISTRY OF LABOR MOBILE INSPECTION GROUP

Since 1995, Special Mobile Inspection Group at the Ministry of Labor (MTE) has led the enforcement of Article 149 of the country’s penal code which defines and prohibits the practice Brazil calls modern slavery. The federal-level MTE teams conduct surprise field inspections, usually in response to denunciations issued by workers, labor rights organizations including CPT, or others. They make their unannounced visits in the company of federal and state police, who provide protection, and state prosecutors collecting information for their own purposes.

When the inspection teams determine that workers have been subjected to conditions analogous to slavery, they carry out a “rescue” operation that requires employers to pay what they owe to workers, who are free to leave their employers and eligible for financial assistance and training to aid their reintegration into the legal economy. To date, Brazil has rescued over 45,000 modern slaves from degrading working conditions.

This work is not for the faint of heart. MTE Labor inspectors have been threatened, attacked and killed in the course of their work over the past two decades.

.

“THE DIRTY LIST”

When MTE auditors inspect farms and firms suspected of profiting from modern-day slavery, their reports trigger a review process that can take up to two years or more. During that time, authorities review the evidence and decide whether or not to include the employers in a federal registry known popularly as the “Dirty List.” Employers that are included in the list aren’t just publicly shamed for two years and shunned by supply chain partners—they also lose access to public finances and are banned by some private banks. At the end of the two years, if they have made the remedial actions required by inspectors, their names are removed. This process is all undertaken by Brazil’s Executive branch and does not constitute a legal conviction. Employers must be tried separately in Brazil’s judiciary if they are to be formally convicted, but few are.

The Dirty List was suspended in late 2014 after an injunction was filed in the country’s Supreme Court. More on that tomorrow.

.

NATIONAL PACT TO ERADICATE SLAVE LABOR

Started in 2005, the National Pact to Eradicate Slave Labor was originally hosted by a working group comprised of four non-profit organizations: Instituto Ethos, a forum for corporate social responsibility in Brazil, the journalist collective Repórter Brasil, the human rights organization Observatorio Social and the ILO. At its height, the National Pact was signed by more than 300 companies representing over 30 percent of Brazil’s GDP, including powerful national brands and the Brazilian subsidiaries of leading multinationals including 3M, Cargill, Carrefour, Coca-Cola, Dow, McDonald’s, Syngenta, Wal-Mart and others. Signatories committed to join the country’s effort to eradicate slavery by eliminating it from their supply chains and ending business relationships with partners on the Dirty List. They also committed to reporting publicly on their efforts.

In 2014, the National Pact process was reengineered and institutionalized in InPACTO—the Institute for the National Pact to Eradicate Slave Labor—a trade association focused exclusively on collaborative efforts among dues-paying members committed to the goals of the National Pact. More on that the day after tomorrow.

.

NATIONAL COMMISSION TO ERADICATE SLAVE LABOR

Finally, a permanent National Commission coordinates all the elements described above—and then some—across sectors as part of a comprehensive five-year plan to eradicate slave labor. (It includes the “Escravo, nem pensar!” campaign whose work is featured in the image above—a multi-faceted awareness campaign that includes print publications, documentaries, radio programs and educational materials for Brazilian schools.) Brazil is in its second multi-year plan now.

.

Over the next two days, we will profile in greater detail two especially important tools in Brazil’s campaign against modern slavery that are undergoing important challenges: the Dirty List and the National Pact to Eradicate Slave Labor.

.

<< Previous: A Little Perspective on the Scope of the Problem

Next: Brazil’s Transparency List >>

– – – – –

This post is the fifth in an eight-part series on the CRS Coffeelands blog about modern slavery in Brazil’s coffee sector. The series draws on research coordinated by CRS and conducted by Repórter Brasil with the generous support of the Howard G. Buffett Foundation and allies working in the coffee sector, including: Allegro Coffee Company, CRS Fair Trade, Fair Trade USA, Equal Exchange, Keurig Green Mountain, Lutheran World Relief, the Specialty Coffee Association of America, United Farmworkers, UTZ Certified and others. The views expressed in this series are those of its author. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the companies or organizations that provided financial support for the research that informed this series.