Before we break Christmas, a reflection on two words we don’t care for when applied to our coffee programming—“well-intentioned” and “naive”—and a perspective from Pope Francis that turns the idea of naïveté on its head.

.

.

“WELL-INTENTIONED” and “NAIVE”

Over the past week and a half, we published this eight-part series on modern slavery in the coffeelands. It was based on evidence we uncovered of reprehensible labor conditions on a small number of coffee estates in Brazil.

Privately, respected colleagues in specialty coffee have characterized our efforts to call attention to those conditions as “well-intentioned” and “naive.”

“Well-intentioned” is an insult disguised as a compliment. Sure, it gives us credit for our good intentions, but it is patronizing in its implication that while we may mean well, we don’t understand how the “real world” works. More specifically, that we don’t understand how markets work. We don’t object to this comment because we don’t believe that development organizations like mine can do harm when they mean to do good. We know there is a real risk of unintended consequences in all fields of human endeavor, which is why we apply the principles of Do No Harm to our fieldwork. Rather, we object to it because we have worked very hard over more than a decade to develop a deep and working understanding of the specialty coffee market so we can help make it work better for smallholders and farmworkers. And because our recent success in creating value for farmers while creating value for industry suggests we have learned a thing or two about how markets work (and how they can work for poor people).

“Naive” is even worse. Less nuanced. The same patronizing tone and the same implication of limited understanding without the obvious credit for good intentions.

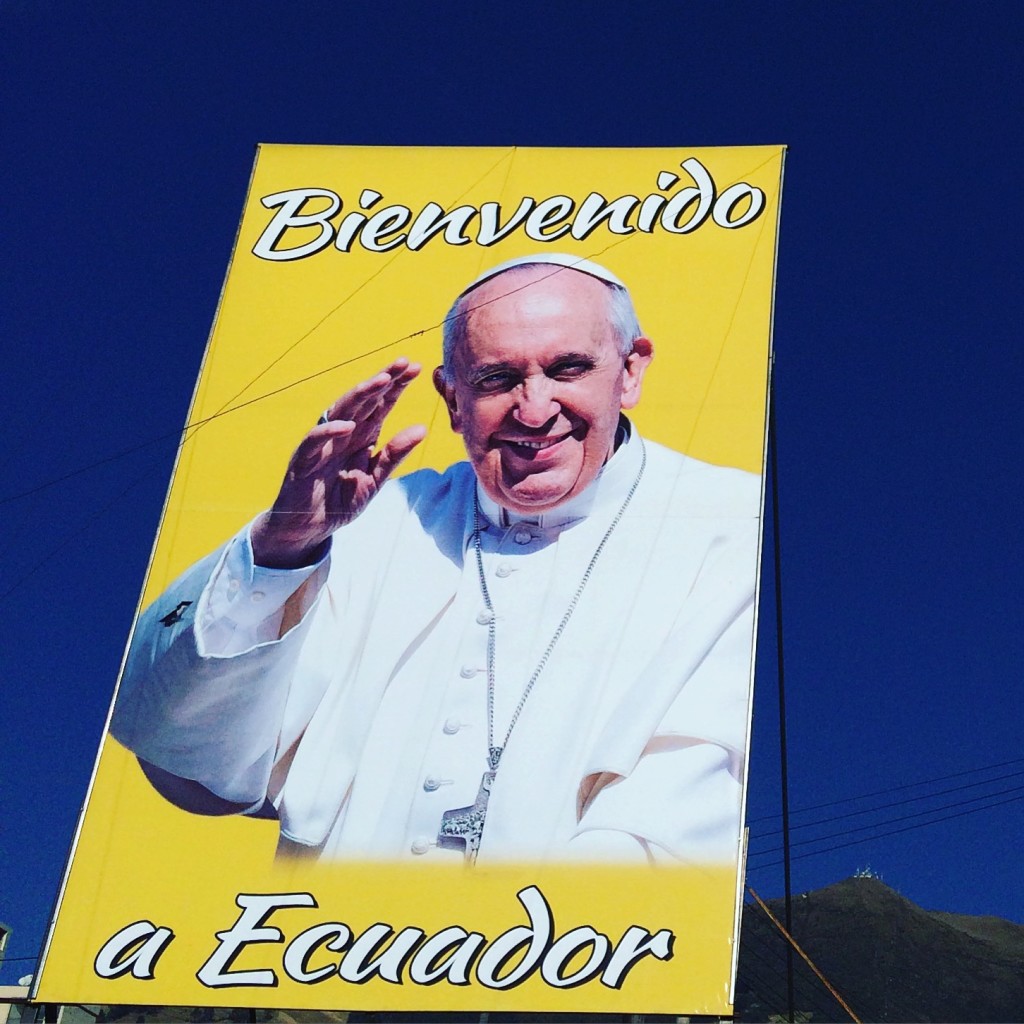

But in the Catholic social teaching that is the wellspring of our inspiration—and in the wisdom of Pope Francis—lies a different perspective on naïveté. One that may absolve us of the charges. Or at least, take some of the sting out of them.

.

THE MOTIVATION BEHIND OUR WORK

Last week, Cooperative Coffees Executive Director Ed Canty weighed in here on the discussion of modern slavery in the coffee sector. In his closing comments, he wrote: “I know CRS does not approach development work from a religious angle.” He is wrong.

We do not preach or proselytize in the field, of course.

But we are part of the Catholic Church and our work is inspired explicitly by what Ed calls “a religious angle.” Our Mission Statement says it plainly: “We are motivated by the Gospel of Jesus Christ.”

.

WHERE FRANCIS COMES IN

The Gospel of Jesus Christ, of course, is pretty historically remote from the conditions in which we work around the world today. Fortunately, Catholic popes have been analyzing contemporary social issues through the lens of the Gospel for nearly 125 years, applying its ancient values to modern challenges and issuing guidance, in the form of papal encyclicals and other writings, on how we might apply those values today. The result is a powerful and progressive body of work that collectively constitutes what we call “Catholic social teaching.”

In 1891, Pope Leo XIII published the first papal encyclical on social issues. It was titled Rerum Novarum (Latin for “revolutionary change”) and it focused on the “Rights and Duties of Capital and Labor” in an industrialized global economy. (Our ongoing communications here about farmworkers in the coffee fields may be new-ish for specialty coffee, but not for the Church: they tap into a long tradition of Catholic social teaching on issues related to labor.) Since then, popes have issued dozens of encyclicals on social issues including economic justice, international development, the dignity of work, war and peace, and the environment.

Pope Francis is heir to this tradition and the author of current Church doctrine on social issues. On many of those issues, he has won admiration within and beyond the Catholic community for messages that are exceptional for their relevance, nuance, principle and humility. And thanks to his active engagement on social media (@Pontifex) he communicates his messages in ways that are uniquely accessible and modern. But on some issues—like economic justice—Francis prefers to kick it old-school.

His encyclical Laudato Si issues a searing indictment of our economic model and urges us to change our ways before it is too late. He pronounces modern slavery and human trafficking crimes against humanity driven by an unchecked pursuit of wealth and power that regards human beings as mere instruments of production and pleasure. And in his Apostolic Exhortation on the economy titled Gaudium Evangelii, Francis invokes the language of the Commandments when he tells us to “Say ‘Thou shalt not’ to an economy of exclusion and inequality.”

In that document, Francis goes on to offer his own take on naïveté:

“Some people continue to defend trickle-down theories which assume that economic growth, encouraged by a free market, will inevitably succeed in bringing about greater justice and inclusiveness in the world. This opinion, which has never been confirmed by the facts, expresses a crude and naive trust in the goodness of those wielding economic power and in the sacralized workings of the prevailing economic system.”

A prevailing economic system that has fueled a race to the bottom that rewards low wages and precarious working conditions.

A prevailing economic system that has concentrated unprecedented fortunes in the hands of a few and failed to stamp out modern slavery or bring an end to poverty or hunger.

A prevailing economic system that seems to accept grotesque income inequality, structural social exclusion and accelerating environmental degradation as the cost of doing business.

We are trying to raise the visibility of workers and raise the bar on wages and working conditions in coffee not because don’t understand how the market works, but precisely because we do. And because we believe that specialty coffee can do better by the smallholder farmers and farmworkers on whom it depends.

If our work on modern slavery in Brazil’s coffee sector is naive, if it is naive to sacralize the human person over the market, then it is an accusation we can learn to live with.