The biggest news in coffee last week did not come out of Portland or Seattle or LA, but out of Washington: President Obama signed the Trade Facilitation and Trade Enforcement Act of 2015 into law. Here’s what it has to do with coffee.

.

.

The Smoot-Hawley Act and the “Consumptive Demand Exception”

The Smoot-Hawley Act, also known as the Tariff Act of 1930, may be more than 85 years old, but the rules it put in place still govern some of our trading practices. Section 307 of that legislation established a prohibition on imports of “All goods, wares, articles, and merchandise mined, produced, or manufactured wholly or in part in any foreign country by convict labor or/and forced labor or/and indentured labor.” But in what we might today call a “loophole,” it also created this exception: “in no case shall such provisions be applicable to goods, wares, articles, or merchandise so mined, produced, or manufactured which are not mined, produced, or manufactured in such quantities in the United States as to meet the consumptive demands of the United States.” In other words, the prohibition set out by Section 307 has never been applied to things we can’t live without that happen to grow in the tropics. Things like bananas, sugar, cacao and, of course, coffee. These items have gotten a free pass. All that ends next week.

.

Section 910

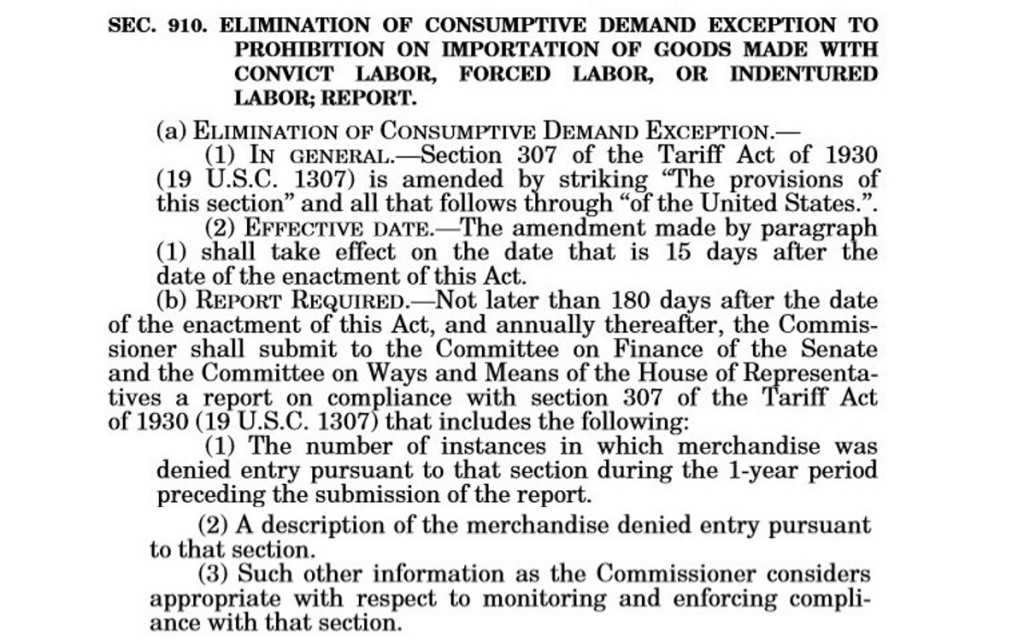

Section 910 of the Trade Facilitation and Enforcement Act of 2015, buried under the inconspicuous header “Title IX—MISCELLANEOUS PROVISIONS,” closes the door on imports of goods produced by forced labor and slave labor. The section has less than 200 words, and the title tells you everything you really need to know about it:

.

.

It does include some other relevant information. It tells us that the effective date of this measure is next week. That this September (and every September after that) the Commissioner of U.S. Customs and Border Protection must send a report to Congress explaining HOW MANY times goods were denied entry due to the new measure, WHAT KINDS of goods, and anything else the Commissioner deems relevant to Congress.

.

What’s it got to do with coffee?

The protection from scrutiny regarding forced labor that coffee has enjoyed since 1930 as a result of the consumptive demand loophole is gone.

What this almost certainly means is that most coffee companies will need to invest more in supply chain transparency and traceability to protect themselves against the risk that their coffee will be on the list of goods denied entry in the U.S. Customs and Border Patrol Commissioner’s annual report to Congress.

What is less clear is how Customs will enforce it.

How will it define convict labor or/and forced labor or/and indentured labor? Will that 1930 language be updated according to 2016 standards? If so, how? Will it include child labor? What Brazil defines as “slave labor?”

However it chooses to define the categories of prohibited labor, will it rely for enforcement on only official U.S. government data, like the U.S. Department of Labor’s List of Goods Produced by Child Labor and Forced Labor? If so, will coffee that comes from a country on the list be rejected outright? Subjected to special scrutiny? Or will Customs require more specific information about the origins of the coffee on the manifest?

Or will Customs also consider information that comes from private sources? Could Section 910 become a tool for human rights activists and modern abolitionists to block entry of goods suspected of being produced by slave labor based on information gathered through private research? Will reports like this one, for example, based on information published by the Danish human rights organization Danwatch, be sufficient to keep coffee from landing in U.S. ports?

These and other related questions have likely already been sent to trade lawyers. The answers those lawyers send their clients will inform the way the coffee industry responds to the new legislation.