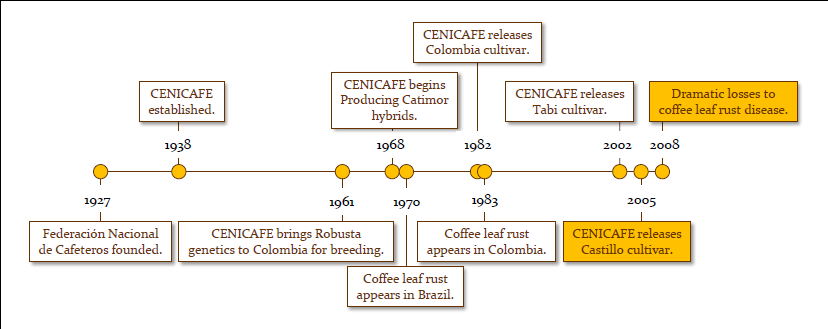

Colombia’s Federación Nacional de Cafeteros is a most remarkable institution. Among the many achievements of which the FNC is justifiably proud is its long tradition of coffee research. The Federation’s first annual budget, way back in 1927, included funding for research into coffee production and disease. In 1938, Colombia established a National Coffee Research Center, CENICAFE. For more than 50 years, CENICAFE has been working on genetic improvement to increase the productivity and resistance of Colombian coffee—a process that has led to dramatic changes over time in Colombia’s coffee supply.

.

Selfie with Huver Posada, the breeder most responsible for developing Colombia’s Castillo variety.

.

During the last half of the 20th century, Caturra was the most common cultivar in Colombia’s coffee fields. It gradually replaced most of the country’s traditional Bourbon and Tipica cultivars because of its higher productivity. Caturra not only produces more coffee per plant than Bourbon or Tipica, but it is also more compact, so farmers can grow more plants in the same area — a good thing for farmers. But susceptibility to disease is in the DNA of Caturra and other traditional Arabica varieties — not such a good thing for farmers.

Arabica coffee has 44 chromosomes (genetically complex) and is self-pollinating (genetically homogenous). The genetic complexity and homogeneity that allows Caturra and other Arabica cultivars to produce cup quality consistently over time and across many different origins also makes them less resistant to disease than those that have more variety in their genetic make-up. Like Robusta.

Robusta coffee has only 22 chromosomes and is not self-pollinating. Its relative genetic simplicity and its genetic diversity — cross-pollination creates a virtually unlimited number of genotypes — mean it is more adaptive and naturally more resistant to disease than Arabica.

In 1961, CENICAFE began research and field trials with Timor — a polygenic coffee cultivar with Robusta genetics. By 1968, CENICAFE had was combining Timor hybrid with the popular Caturra cultivar to create lines of Catimor, a high-yielding, highly resistant variety first developed in Portugal and now widely grown in Central America. After five generations of breeding and selection in the Catimor line, CENICAFE released its Colombia cultivar in 1982, highlighting its productivity, cup quality and resistance. When coffee leaf rust was observed in the country’s coffee fields in 1983, promotion of Colombia was a key part of the Federation’s response. Over time, the Colombia cultivar gained ground (literally) at the expense of Caturra and other traditional varieties.

.

But CENICAFE’s breeding with Robusta genetics didn’t stop there. In 2002 it introduced the Tabi cultivar. In 2005, it released Castillo along with research showing across-the-board improvements over the Colombia and Tabi cultivars in productivity, disease resistance and cup quality. This last claim continues to be the subject of some disagreement between the Federation and quality-focused roasters around the world. But when production losses to coffee leaf rust spiked beginning in 2008, the Federation began a massive campaign to replace traditional cultivars with Castillo.

– – – – –

This post is the third in a seven-part series titled “Colombia’s other eradication campaign.”

<< Previous: Colombia and coffee leaf rust.

Next: Farmer perspectives on Castillo. >>