Our work in the coffeelands over the past 10 years has focused on small-scale family farmers, but we recognize that the seasonal laborers who pick coffee, often migrants, are arguably the most vulnerable actors in the coffee chain. And there are a lot of them. According to PROMECAFE data, more than 1.7 million people work on the annual coffee harvest in El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua. The harvest is normally the most reliable and profitable source of work for unskilled labor in the coffeelands, but this year there wasn’t enough work to go around. Next year, by all accounts, it is going to be even worse.

As we plan a response to the coffee leaf rust crisis in Central America, we are working to get a better handle on a population we haven’t historically served, and a clearer sense of the impacts of the crisis on farmworker income.

The International Coffee Organization (ICO) released its report on the coffee leaf rust epidemic in Central America earlier this month, citing official (and updated) figures from PROMECAFE on the impacts of the outbreak. They include estimates of the number of jobs lost and the total economic losses to rust in the countries mentioned above (220,444 and $465 million, respectively), but there are no official numbers regarding the economic losses to farmworkers specifically.

Today, we advance some rough working estimates for the first time.

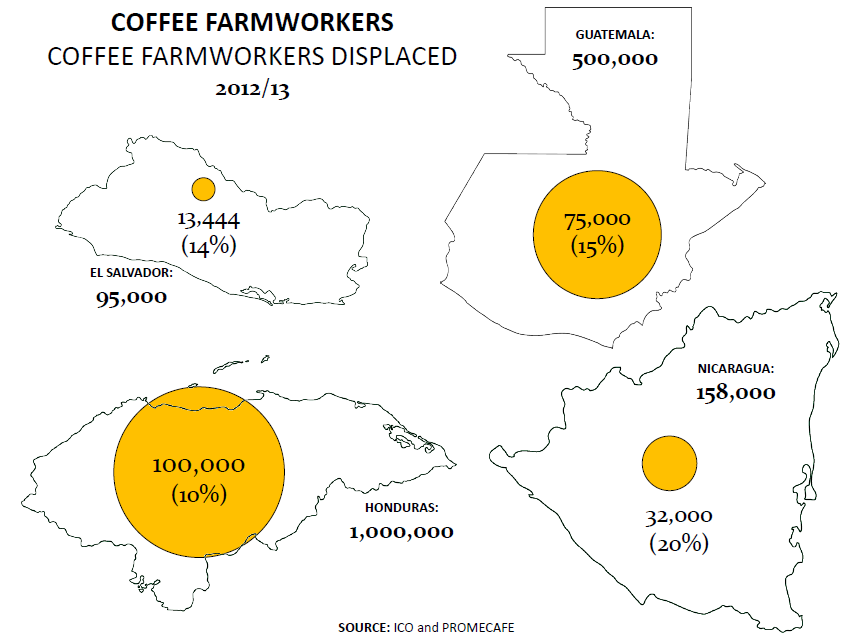

FARMWORKER EMPLOYMENT

- 2012/13

According to the ICO and PROMECAFE, nearly a quarter of a million people were out of work this harvest in El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua, the four Central American countries where CRS is working in the coffeelands. This graphic shows the total number of coffee farmworkers in each country, the number who were displaced this year as a result of the coffee rust epidemic, and the percentage they represent of the total coffee work force.

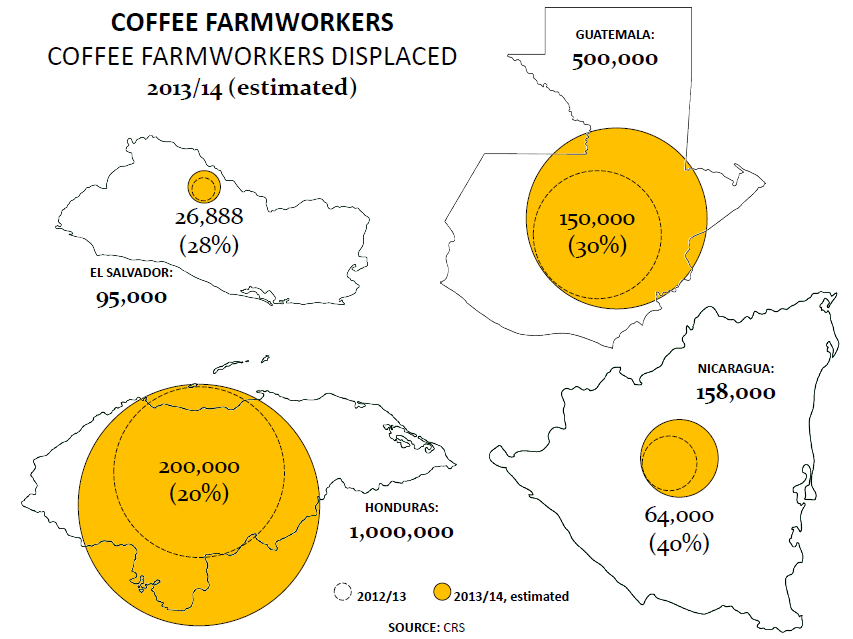

- 2013/14

Neither ICO nor PROMECAFE have advanced any projections for job losses during the 2013/14 harvest, but official data on coffee production seem to be converging around the idea that production losses next year will be twice what they were this year. Anacafé in Guatemala estimates losses for the 2012/13 harvest at 15 percent and has projected losses of 30-40 percent for the 2013/14 harvest. IHCAFE in Honduras also reports that its losses could double next year. With production losses doubling next year, we can expect to see demand for seasonal labor reduced by twice as much as it was this year. And indeed, FEWS NET is estimating labor demand will be down by as much as 30-40 percent for the next crop year after estimating a 15-20 percent reduction in labor demand during this harvest. In the CA4 countries mentioned above, it could look something like this.

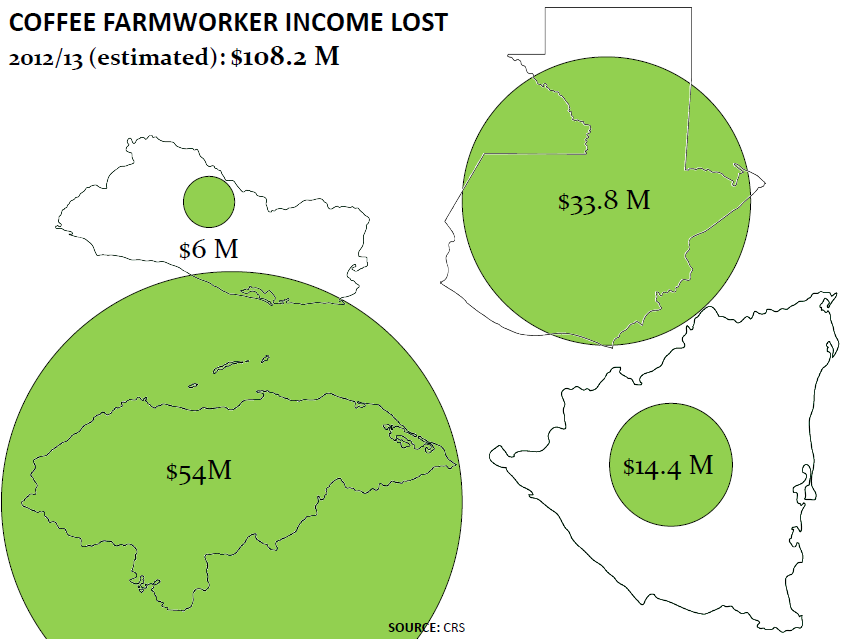

FARMWORKER INCOME

So we have an idea of how many coffee pickers are struggling this year and a rough estimate of how many will be displaced next year if current projections for production losses and reduction in labor demand hold. But what does this mean in terms of lost income for coffee workers and their families?

- 2012/13

Based on discussions with colleagues from Central America who work in the coffeelands, we estimate that under a “full-employment” situation, a coffee picker may work 90 days per year. With average daily earnings of coffee pickers in the region between $5-$6 a day, that is $450-540 a year per farmworker. In many households, 2 or 3 people may work on the harvest, meaning that coffee picking can mean up to $1,000 a year or more for households that may earn barely twice that amount in an entire year. Based on the assumptions of a $5 workday ($6 in Honduras) and 90 days of labor during a harvest season, and using the official ICO/PROMECAFE data, we estimate the economic losses to coffee laborers for the 2012/13 harvest at over $100 million.

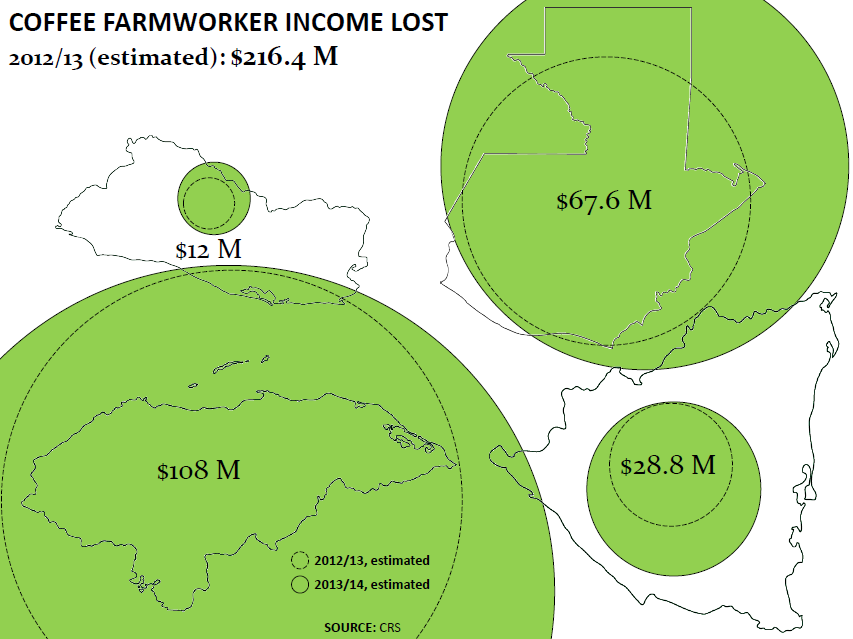

- 2013/14

Applying the same formula to income projections as we did to estimate job losses for 2013/14 doubles the value of the losses across the board.

These estimates are very rough. This is particularly true of the 2013/14 estimate, which assumes price levels identical to those that prevailed during the 2012/13 harvest. But in the absence of official data, these initial informed guesses can help us get a sense of what it may take to make farmworkers whole next year.