Last November, the pioneering Colombian exporter Virmax published these photos from Oswaldo Acevedo’s Hacienda El Roble and wondered whether there is a strand of yellow Maragogype out there despite the science that says Maragogype produces only red cherry.

Does yellow maragogype exist? Or is this another variety? @HdaElRoble pic.twitter.com/U1xblfMX2v

— Virmax Café (@virmaxcafe) November 6, 2013

Since then, I have been pulled into a rich conversation with related to yellow Maragogype, but one that revolves less around genetic curiosities than smallholder farm economics.

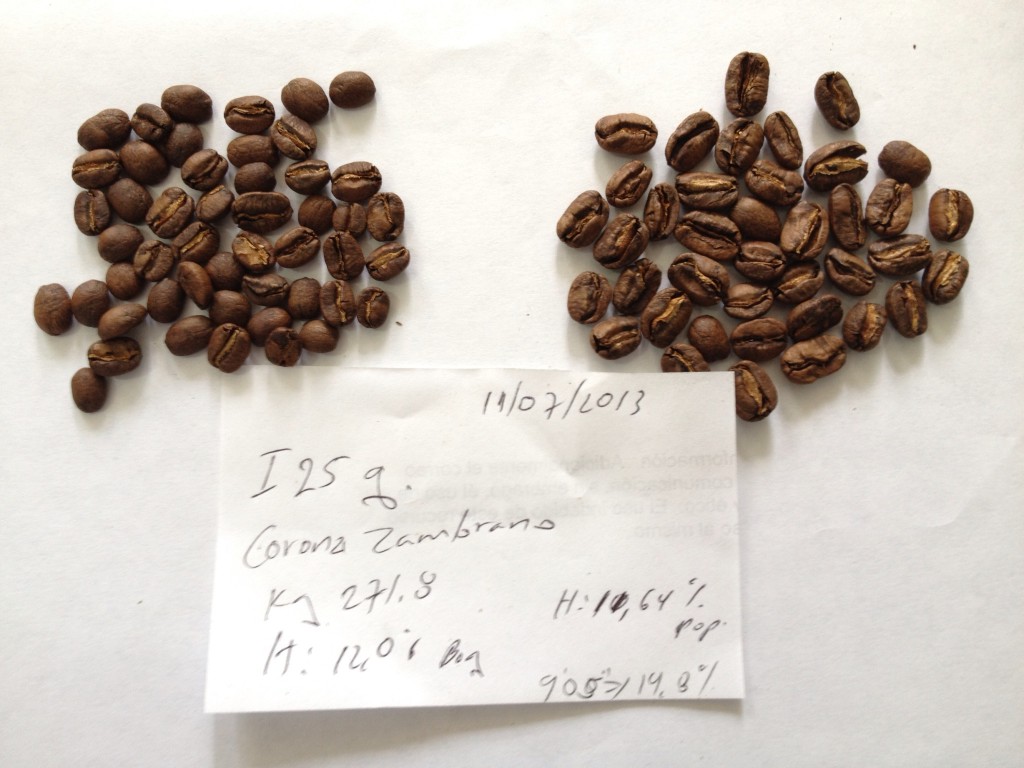

Virmax has been participating in our Borderlands Coffee Project over the past few years, exporting single-farm lots from participating growers for several different U.S. roasters. When it cupped last year’s lot from Corona Zambrano’s farm in Nariño, it separated out some unusually large beans that it was sure were Maragogype.

Earlier this year I visited Doña Corona’s farm to investigate, and did indeed find a small cluster of what appeared to be Maragogype, including some yellow cherry.

Since then, I have been hooked by the case of the yellow Maragogype, but concerned more with cracking its economics than its genetics. In a marketplace where there is growing demand for exotic varieties like Maragogype, what are the opportunities for participation and profit for smallholders like Doña Corona?

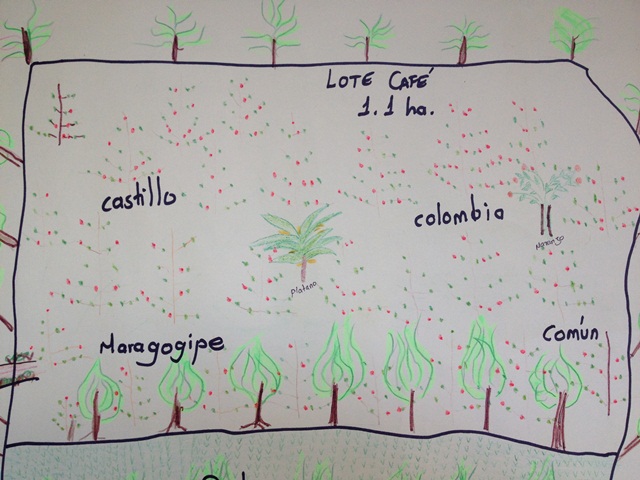

After our visit, we worked with Doña Corona to map her farm. In addition to the 1.1 hectares mapped here, she has another 1-hectare coffee plot planted with Castillo, sugar cane and tilapia ponds.

Her Maragogype plants were about 15 years old. They had not been particularly well cared for. She told me she was planning to rip out the whole lot and replant with Castillo. I asked her to hold off on making a final decision about what to do with the coffee until I could bring some U.S. roasters and Colombian exporters to the farm to share their perspectives.

In May, members of the Borderlands Coffee Project’s Advisory Council visited Doña Corona on her farm. What was clear to everyone was that the plants in their current state are not serving anyone well–not Doña Corona or any of her potential downstream trading partners. She needs to make that part of her farm more productive. What was less clear was how. Stumping? Replanting with Maragogype? Replanting with Castillo? Some combination of these? Which approach would be best for her? Which approach would be best for roasters? Was there an approach that fairly balanced the risks and opportunities of both parties?

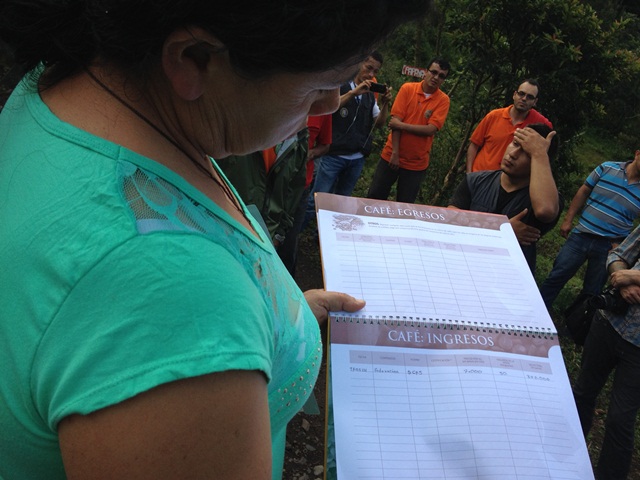

These decision points are vitally important for smallholder farmers like Doña Corona, who must provide for her family with what she earns from her 3.5-hectare farm. The decision she makes this year about what to do with her Maragogype grove will affect her family’s fortune for years to come. We are helping her and other project participants understand make weighty decisions like this one on the basis of better information. One aspect of that effort is helping them understand their margins for the first time, carefully recording all expenses and revenues in field ledgers like this one.

In these Cuadernos de Cuentas, Doña Corona and other participants in our Borderlands Coffee Project are carefully registering every expense incurred in coffee production and every sale of coffee to calculate the returns on their investments in coffee.

Another aspect of that effort is helping bring growers together with the roasters who buy their coffee so they get market signals with no distortion. In this case, we were able to do both: to help Corona sketch out some rough numbers and to bring market voices to bear on the discussion.

Stumping the current plants or replanting with Maragogype seedlings could generate strong production in 3-4 years’ time. But Maragoype is susceptible to coffee leaf rust and other diseases in ways that Castillo is not.

Even if Doña Corona does effectively manage disease, she is destined to acheive lower yields with Maragogype than Castillo–Maragogype plants are large and must be planted at low densities, meaning there are fewer plants per hectare; they also have infamously low rates of productivity, meaning that each plant will produce less cherry.

If Doña Corona plants Maragogype at 1/2 the density of Castillo and achieves 4/5 the yield of Castillo (both ambitious objectives) she will generate 2/5 the production. That means that she will have to earn 2.5 times more for her Maragogype than she does for her Castillo to justify the decision to plant it in the first place. While she may be able to command $2.50 for a high-grown Maragogype in a $1 market, it is harder to imagine her fetching $5 a pound in a $2 market.

In the end, we agreed that keeping Maragogype in the mix only makes sense if Doña Corona is willing and able to process it separately (and well). If the coffee is good enough to earn the kinds of premiums that can compensate for the productivity losses. And if she has ready access to a buyer willing to pay those kinds of premiums. We knew the first and last were true, but weren’t sure about the second. As luck would have it, we had prepared a sample of her Maragogype for a cupping scheduled the day after the farm visit.

Geoff Watts of Intelligentsia Coffee cups Doña Corona’s Maragogype sample the day after we visited her farm.

The next day at the cupping table, the results were unambiguous. Six of the 10 tasters rated Doña Corona’s Maragogype sample the best coffee of the day. It netted the highest single score (91 points) and the highest average score (87.75) of the 12 coffees presented.

The results of the cupping introduce more nuance to the plot of the yellow Maragogype story.

On the basis of the strong cupping results, roasters encouraged Corona to keep some land devoted to Maragogype, and to consider a diversified approach to varietal selection that blends the objectives of mitigating production risk and maximizing market opportunity.

Over the short-term, Doña Corona will separately harvest and process her Maragogype in the hope of bringing 2-3 bags to market this harvest for a premium. Over the medium-term, she will renovate the part of her farm where her Maragogype plants are now. She hasn’t committed to Maragogype or Castillo, but has given herself (and her neighbors) some options: she has selected Maragogype seed and started propagating it at her farm, and provided Maragogype seed for a community seedbed managed by the students at the Saint Francis of Assisi Institute.

I see Doña Corona’s yellow Maragogype story as emblematic of the challenges and opportunities facing smallholder coffee growers around the world. We will publish the next chapter in that story after she harvests her coffee.